The Call You Don’t Want to Take

Monday morning. Nothing looks broken—just uncomfortable. Screens are red, but not apocalyptic. The position is down, but not fatal. Then an email pops up—polite, brief, and non-negotiable: “Please post additional collateral by 2:00 p.m.”

No one calls that a crisis. Not yet.

But in the derivatives world, that message is often the dividing line. A market move turns into a contractual event. Prices can fall, spreads can widen, volatility can jump—those are still “market phenomena.” Once the collateral clock starts, the move becomes an obligation. And the story stops being about forecasts and starts being about deadlines: what you can post, what qualifies, where it sits, and whether it can arrive in time.

That’s why the post-COVID era keeps dragging ISDA and CSA terms out of the back office and onto the front page. In calm markets, they read like paperwork. In stress, they decide outcomes.

In the prior piece, “Why Are ISDA, CSA and IM Relevant to You?”, the focus was on why the framework matters. Here we push the lens forward: when markets seize up, funding tightens, and counterparties begin to worry about counterparty risk, how does the framework get “activated”—and how, within hours or days, can it rewrite risk allocation and outcomes?

I. ISDA Isn’t a “Default Manual.” It’s a Risk-Forward Machine.

Many investors think ISDA becomes relevant only after something has gone wrong—after a counterparty fails, after a default notice lands, after the headlines. That’s true, but incomplete. ISDA and its credit support architecture matter most because they pull risk forward—before insolvency, before court filings, before the narrative has time to settle.

In derivatives, risk doesn’t arrive neatly at maturity. Exposure is marked-to-market every day—sometimes more often—and it can expand violently when markets gap. Traditional contract law is built around after-the-fact remedies: breach, damages, litigation. Derivatives markets don’t have the luxury of that timeline. So the market built a different kind of contract: one that forces early recognition of losses through collateral mechanics.

That’s the temperament of a CSA. It doesn’t care whether your long-term thesis is sound, or whether the market is behaving “normally.” It asks one question: is the current net exposure covered by collateral—now—and can you deliver within the agreed window? You can be solvent on paper and still be pushed into crisis because you cannot mobilize eligible collateral quickly enough. In stress, the most common disaster is not “sudden insolvency.” It’s “sudden lateness.”

Sometimes the entire arc from market volatility to existential pressure is only one email away.

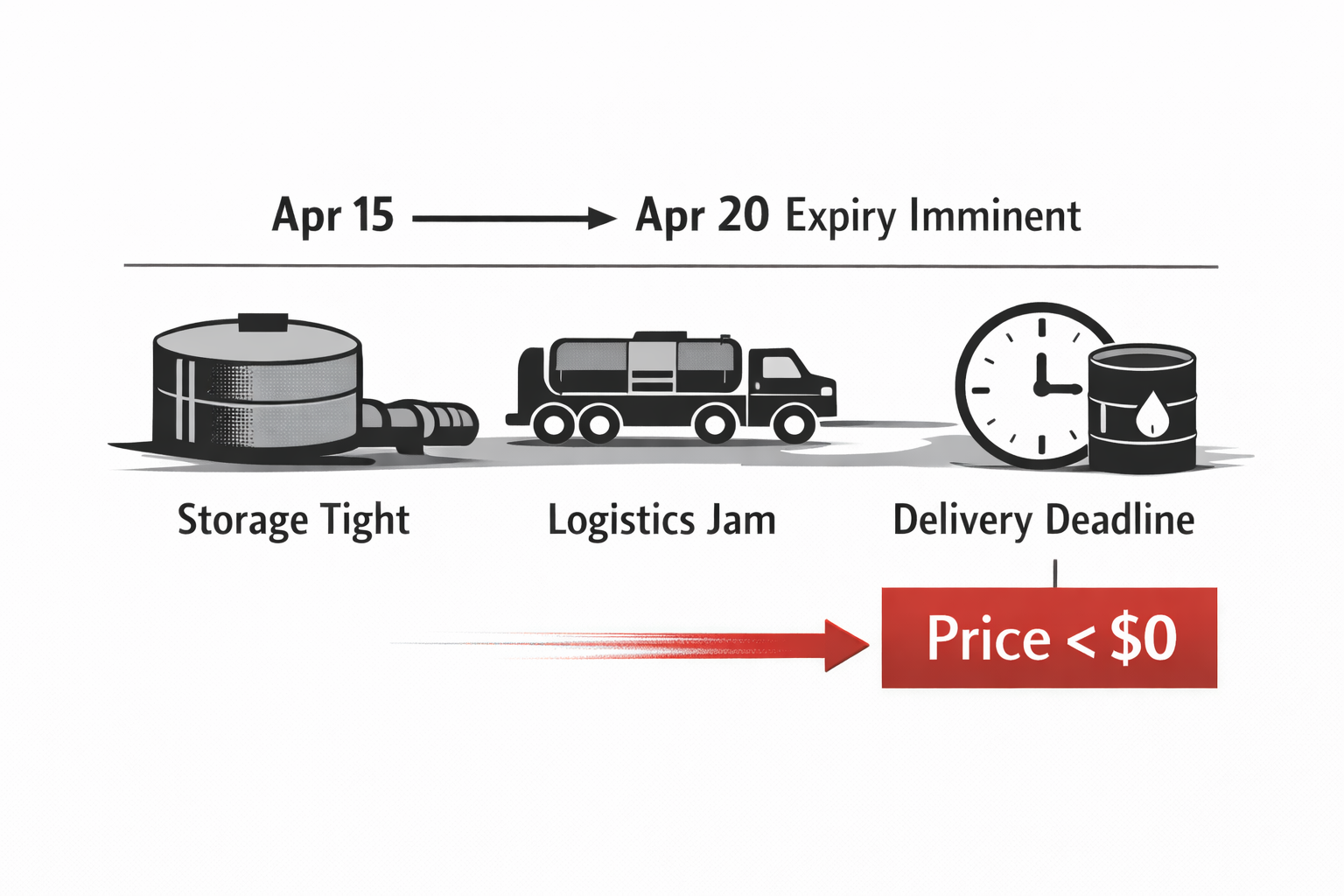

II. 2020: Negative WTI—When Prices Lose Common Sense, Contracts Still Run on a Stopwatch

On April 20, 2020, NYMEX WTI crude’s May 2020 futures contract settled at -$37.63 a barrel. The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission later issued a staff report centered on the May contract’s expiration dynamics and the circumstances that produced the first negative settlement in the contract’s decades-long history.

The market explanation is now familiar: pandemic lockdowns crushed demand; supply didn’t adjust fast enough; and at the delivery point, storage and logistics became binding constraints. But to understand why the price went negative, it helps to re-insert the physical reality that financial markets often abstract away. The front-month WTI contract is physically deliverable. As expiry approaches, holders who don’t close out need the capacity to take delivery and manage storage and transport. When storage is scarce and time is short, the contract begins to behave less like a clean financial price and more like an obligation with a ticking clock. A negative price, in that context, is not mystical. It’s the marginal cost of getting rid of the obligation.

For ISDA/CSA readers, the deeper lesson isn’t the novelty of negative pricing. It’s what the episode did to three quiet assumptions that normally live in the background.

First: valuation stops being a technical detail and becomes governance.

In normal ranges, valuation disputes can feel manageable, because the market provides enough reference points to keep disagreements small. When price moves into territory your systems never assumed could exist, choices that used to feel operational—what source, what method, how to treat outliers—suddenly become outcome-determinative. Under a CSA, those choices feed directly into how much collateral is called.

Second: liquidity gets dragged forward.

The more disorderly the market, the harder it is to finance, to unwind, to turn assets into cash. But margin calls arrive precisely at that moment. You can still believe, economically, that the position “makes sense.” Contractually, you still have to deliver.

Third: time becomes the real underlier.

Negative oil was a wake-up call that markets can lose common sense, but contracts don’t lose cadence. You may not have time to debate whether a price is “reasonable.” The cutoff hits first. And once it does, the risk isn’t “how ugly the mark looks.” It’s “whether you can move eligible collateral to the right place before the clock runs out.”

That’s the first rule of post-COVID market stress: crises often don’t begin with being wrong. They begin with being late.

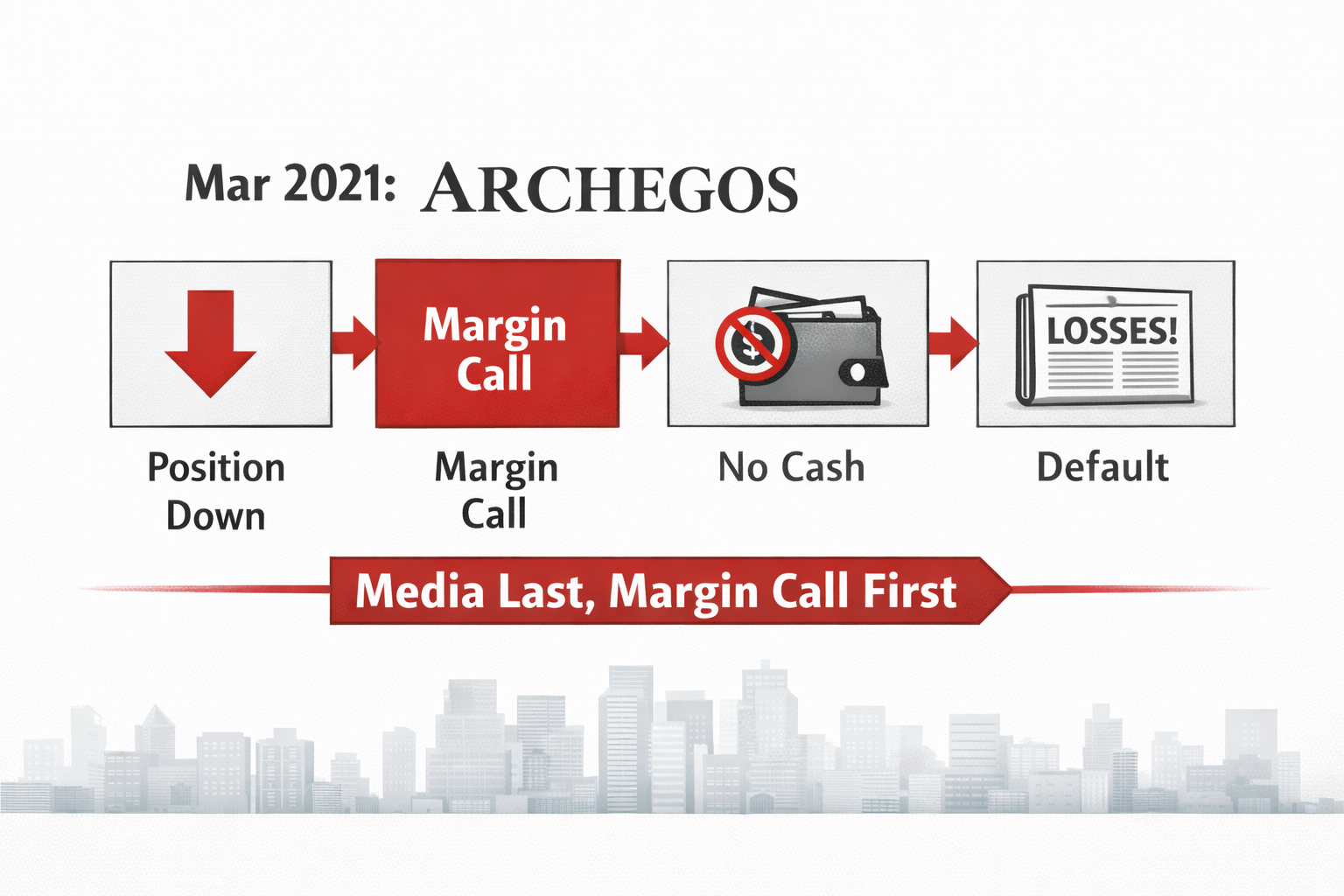

III. 2021: Archegos—Margin First, Headlines Later

If negative WTI was a story about structure and constraints snapping pricing, Archegos was a more classic financial drama: leverage, concentration, a drawdown—and then margin calls that effectively locked in the ending.

Archegos Capital Management, run by Bill Hwang, was a U.S. family office that built large exposures using instruments including total return swaps. In public filings and announcements, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission described a blunt sequence: as Archegos’s most concentrated positions fell in March 2021, the declines triggered significant margin calls. Archegos could not meet them. Default followed. Counterparties suffered billions of dollars in losses.

Archegos is instructive because it puts the ISDA/CSA logic on full display: markets can move, but the contract recognizes margin; once the top-ups stop coming, a “position” can instantly become a “disposal.”

It’s tempting to think crises run in this order: default first, liquidation second. Collateralized derivatives often reverse the timeline. The sequence is usually: price move, valuation move, margin call, funding test—and only then does “default” become visible. By the time the word appears in a headline, the critical moment has often passed: the moment the margin call was issued and the cash didn’t arrive.

This is where legal and financial logic overlap. Margin mechanics convert risk into an immediate delivery obligation. A loss can be economically tolerable if you can finance it and wait for conditions to normalize. A CSA doesn’t forbid waiting—but it makes waiting conditional on collateral coverage. Leverage, in that world, doesn’t just magnify P&L. It magnifies dependence on liquidity and operational capacity.

And once a counterparty fails to meet calls, behavior shifts. Counterparties stop managing price risk and start managing counterparty exposure. They reduce positions, cut risk, and protect themselves. Individually, that’s rational. Systemically, it can accelerate selling, depress prices further, and deepen losses. Many “blowups” aren’t driven, in their decisive phase, by macro narratives. They’re driven by contract mechanics: margin calls make exits crowded, and crowded exits make exits expensive.

That is why so many post-mortems sound the same. “We weren’t insolvent,” people say. “We just ran out of liquidity.” Under ISDA/CSA mechanics, that’s not a contradiction. It is the modern template.

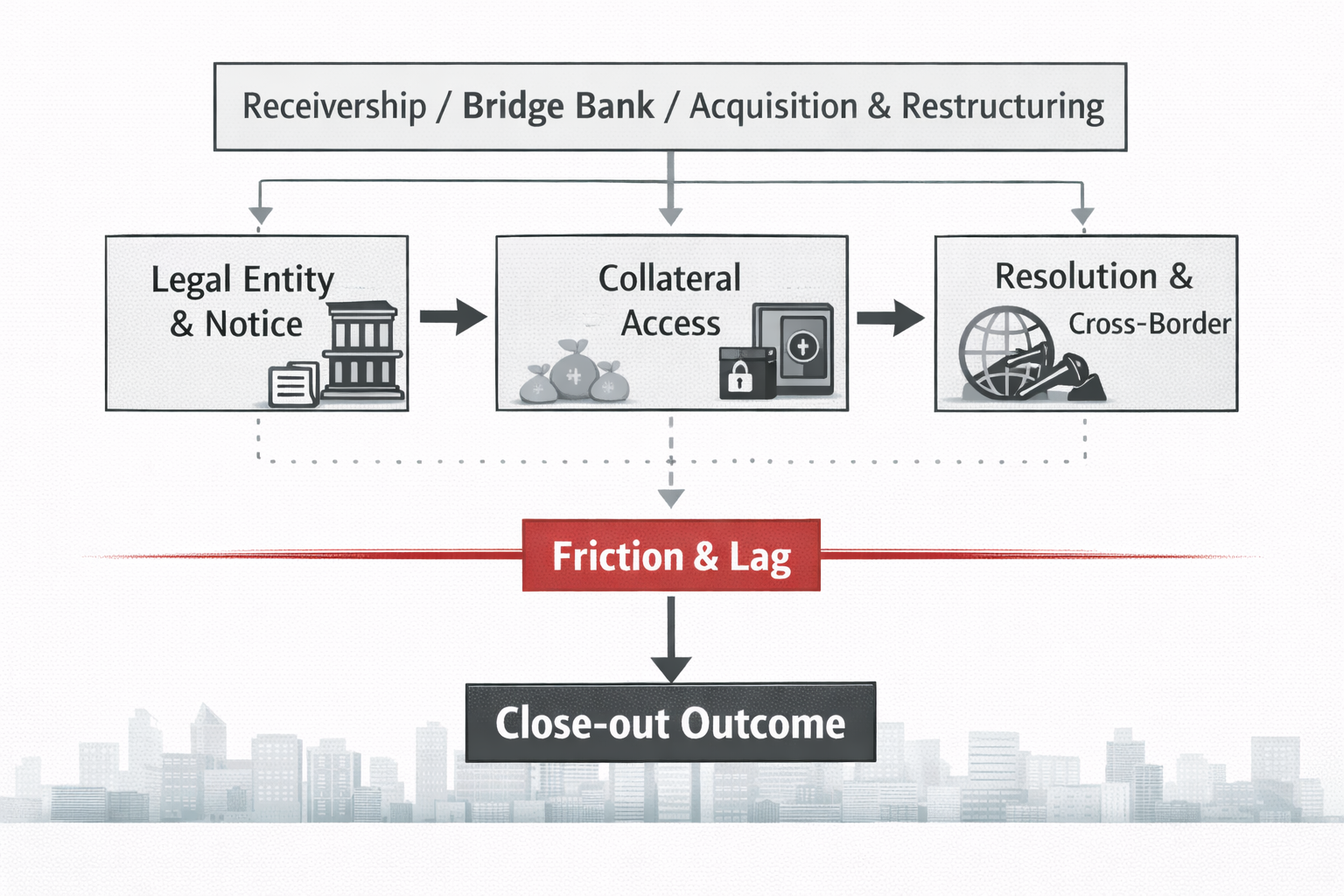

IV. 2023: SVB, Signature, Credit Suisse—Why Close-Out Isn’t a Button

The first two episodes show how stress can run from market prices into margin calls. In 2023, the market confronted a different fear: even if you have the contractual right to terminate, you may not be able to turn that right into an immediate result. Close-out is not a button you press. It’s a path—and in real crises, that path can be interrupted by resolution regimes, custody structures, cross-border frictions, and operational constraints.

In the U.S., Silicon Valley Bank was closed on March 10, 2023 and the FDIC was appointed receiver. Signature Bank followed two days later, with the FDIC again appointed receiver and a bridge bank structure established to maintain continuity and facilitate an orderly resolution.

In Switzerland, the weekend of March 19, 2023 produced a different kind of shock: Credit Suisse was acquired by UBS in a government-supported transaction framed explicitly as a stability measure. Swiss authorities and the Swiss National Bank publicly described extraordinary liquidity and support arrangements aimed at preventing a disorderly outcome.

In moments like these, market focus shifts quickly from “who defaulted” to something more immediate: can we settle, can we access collateral, can we shut the risk down? The anxiety is not theoretical. A weekend event becomes a Monday-morning decision. Your counterparty may no longer be “a bank” in the ordinary sense. It may be an institution in receivership, a bridge entity, or a firm absorbed under emergency measures into a new group structure. At that point, the question is not just whether you can terminate in principle. It is whether the operational and legal mechanics line up: who is the right legal entity now, where does notice go, what can be enforced immediately, what sits in custody structures you can’t touch, what gets delayed by resolution tools, what becomes cross-border.

Without clean answers, the familiar story—terminate, net, close the book—can become more wishful than real. Close-out isn’t a button. It can be a sticky process that unfolds under pressure and gets interrupted by reality.

That context helps explain why ISDA in 2024 published a Close-out Framework, explicitly positioning it as a tool informed by the 2023 failures of SVB and Signature and the Credit Suisse–UBS transaction—events that forced market participants to think about close-out readiness not as a legal abstraction but as a practical necessity.

It also loops back to the opening email. In stress markets, outcomes depend not only on whether you can meet margin calls on time, but on whether—when things move into termination territory—you can translate contractual rights into real risk containment. Rights on paper are not always rights on demand. And that uncertainty can feed back into behavior earlier in the cycle: tighter margining, faster de-risking, less patience.

Conclusion: In Stress Markets, Paperwork Stops Being Paperwork

Taken together, these episodes share a single spine. In stress, contracts don’t pause because markets are abnormal. If anything, they execute more quickly and more strictly. Negative oil reminded markets that structure can break while collateral clocks keep running. Archegos showed how margin calls can decide outcomes before “default” becomes a public label. And 2023 underscored that even after triggers, close-out is not frictionless—it is a process, and preparation matters.

So the most important question isn’t “do we have ISDA in place?” It’s “do we understand how it behaves when markets stop cooperating?” In calm markets, many provisions look like formality. In stressed markets, formality becomes outcome—and the outcome is often determined long before anyone files for bankruptcy.