China’s Solar PV Industry in a Reconfigured Global Power Landscape

Over the past two years, solar PV has felt less like a normal industry cycle and more like a collective health check. The numbers look great on paper, yet the market experience has been far less comfortable. Installations keep breaking records, technology continues to iterate faster, and supply-chain efficiency is being pushed to the edge — where margins still look “fine,” but the math is increasingly tight.

Investors talk about long-term potential, while being repeatedly reminded by short-term price pressure and cash-flow realities. Policymakers, meanwhile, are shifting their tone toward discipline and constraints. Companies are forced to navigate between supply inertia and a changing demand rhythm. As a result, the same question keeps coming back: is the solar story still intact — only entering a new chapter — or has the narrative itself fundamentally changed?

1. Global Energy and Power Demand

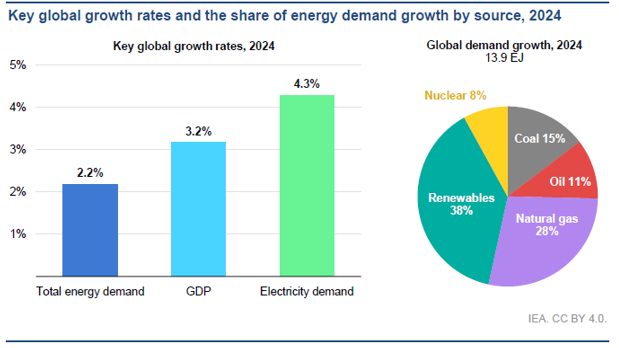

From the perspective of global primary energy consumption, fossil fuels still dominate. Oil, coal, and natural gas continue to account for most of the total energy use. Renewables are growing, but their share of the overall mix is still rising slowly. In other words, the core contradiction of the global energy system has not fully shifted from “fossil fuels” to “renewables.” What we are seeing is more of a marginal adjustment within an existing structure.

However, the picture changes significantly when we shift from primary energy to the electricity system. Global end-use consumption is becoming increasingly electrified. Transport electrification, electric heating, industrial substitution, and the expansion of the digital economy are making electricity the primary carrier of incremental demand. Global electricity consumption has already reached the scale of 30,000 TWh, and in recent years it has shown stronger growth resilience than total primary energy consumption. A terawatt-hour (TWh) is a unit of electricity equal to one trillion watt-hours. For context, 1 TWh roughly corresponds to the annual electricity consumption of about 100,000 average households in developed economies.

For 2026 and onwards, forecasts generally expect global electricity demand to grow by around 4% (could accelerate due to demand of power from AI implementation), implying continued pressure on grids and system flexibility. At the same time, the supply side is also changing. Incremental generation increasingly comes from low-carbon sources. But grid investment and system dispatch capability are becoming the key variables that determine how efficiently power can be delivered.

This friction between rising demand and system constraints is particularly visible in several developed economies. Even as new generation capacity continues to increase, the slow build-out of transmission, lengthy permitting processes, land constraints, retirement of traditional baseload capacity, and regional mismatches in supply and demand are making “not enough power” shift from a risk scenario into a real-world constraint.

At this stage, demand growth itself is not scarce. What is scarce is the system’s ability to deliver stable electricity at controllable cost. The bottleneck is increasingly likely to come from grid expansion and dispatch efficiency, rather than from any single generation technology.

2. Solar’s Structural Rise: From a Manufacturing Race to a Power-System Race

2.1 The Fastest Expansion Curve in Modern Power History

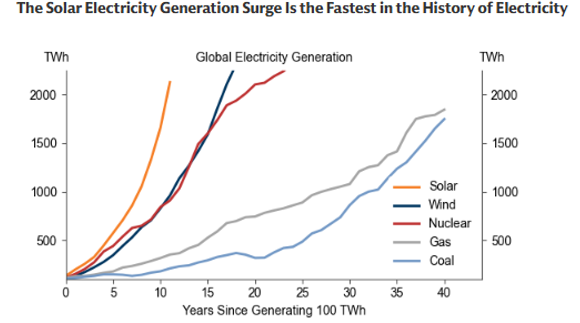

In just over a decade, solar has moved from a fringe technology to the fastest-expanding energy source in modern power history — and the growth is still accelerating.

Even as China and the US begin to reduce policy support at the margin, this wave of solar expansion remains clearly structural. It is not simply the result of subsidies. Instead, it is driven by a combination of:

• a powerful learning curve (cost declines by 20% for every doubling of cumulative output),

• near-zero marginal fuel cost,

• and highly modular, scalable deployment.

These factors continue to compress investment costs and have also helped solar gain broad support under energy security and decarbonization objectives.

2.2 Policy Support Is Softening, but Growth Continues

Against this backdrop, even with policy support weakening in China and the US, it is still necessary to reassess what is driving Solar’s rapid expansion and what the forward path looks like. Since entering its acceleration phase, solar reached roughly 2,129 TWh of annual generation in only 11 years — making it the fastest-growing energy technology in power history.

Although we recently lowered our global installation forecasts due to China’s policy adjustments, our overall view remains growth will slow, but it will continue. By 2030, global annual PV installations are still expected to reach around 914 GW, roughly 57% higher than current levels.

In China, the government has removed the default grid-connection mechanism for new large-scale commercial and industrial PV projects and has also reduced guaranteed offtake volumes and pricing arrangements for certain new-energy projects.

In the US, the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” is likely to have limited near-term impact on project development, as most projects have already locked in tax credit eligibility through safe-harbor provisions.

2.3 Why Solar Is Not a Cyclical “Boom Story”

At a deeper level, solar is not a cyclical boom. It is a structural technology diffusion process.

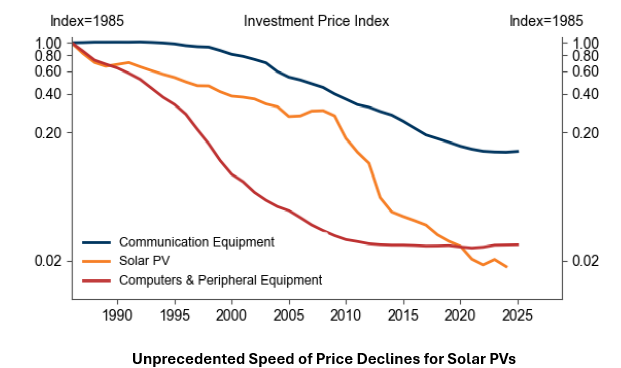

First, the learning curve continues to reduce PV system capex. As cumulative output doubles, costs fall by about 20%, creating a self-reinforcing loop: lower costs → more deployment → even lower costs.

Notably, PV module investment costs have declined faster than computers and communication equipment, making solar one of the fastest price-declining investment goods in modern economic history.

Second, Solar’s marginal fuel cost is essentially zero. This gives it a natural cost advantage in long-term power-market competition.

Third, PV’s modular nature allows rapid deployment in small units at relatively fixed prices. This supports the growth of distributed energy systems and contrasts sharply with large-scale thermal or nuclear generation, which typically requires high upfront capex and long lead times. The combination of zero marginal cost and modularity also strengthens Solar’s appeal in energy security and decarbonization discussions.

3. China’s Solar PV Industry Landscape

As a low marginal-cost and highly replicable generation technology, solar continues to increase its penetration in a global power system undergoing both decarbonization and electrification. Its growth is no longer simply about cumulative installation numbers. It is increasingly tied to new-load growth, capital expenditure direction in power systems, and supply-chain security considerations.

From an industrial perspective, global PV manufacturing is geographically concentrated. Across upstream polysilicon, wafers, cells, and module manufacturing, Chinese companies dominate most segments. The result is a highly integrated, scaled, and cost-competitive supply chain.

Overseas markets remain more demand- and application-driven. Europe, the US, and emerging markets represent the main sources of incremental installations. But in manufacturing, these regions still rely heavily on imports, with local capacity playing more of a supplementary role.

China’s PV industry today is defined by the coexistence of two realities:

1. China remains the global supply hub.

The high degree of industrial clustering and vertical integration — from upstream to modules — creates structural scale and cost advantages. This keeps China as the critical supplier for global incremental installations and exports.

2. The industry is also under near-term “clearing pressure.”

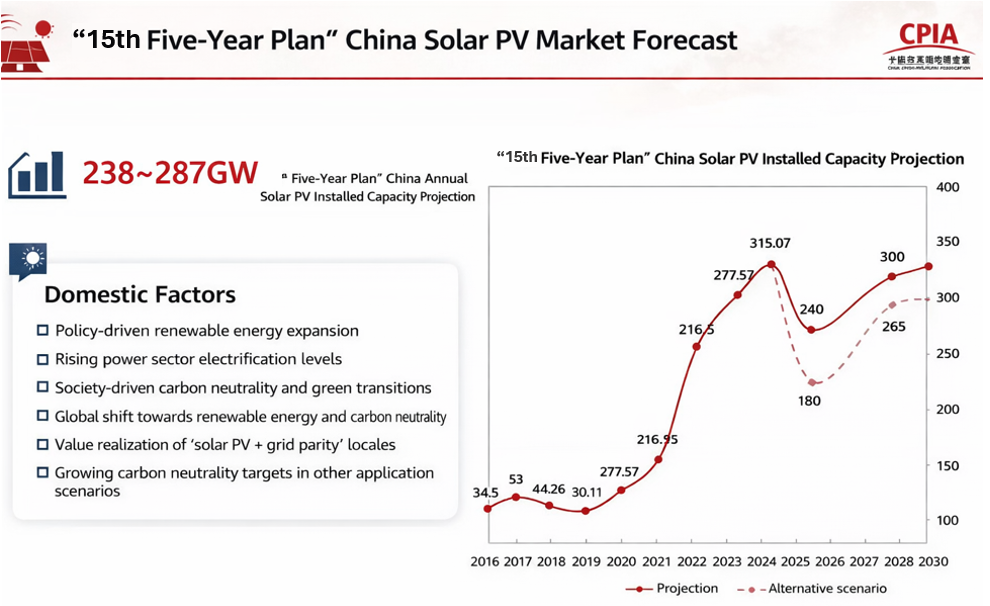

Installation growth is shifting from a high-growth phase back to a more sustainable range. China’s new installations reached 315.07 GW in 2025 but could slow to 180–240 GW in 2026. From 2027 onward, installations may return to an upward trend, reaching 270–320 GW by 2030. This implies near-term slowdown, but long-term demand still has a solid base.

In this phase — where incremental demand slows while supply inertia remains — policy messaging around “anti-involution” (anti-destructive competition) has become more explicit.

The governance of excessive price competition has been listed as a key priority for 2026. The policy toolkit is expected to include capacity control, standards and quality regulation, pricing enforcement, and measures aimed at preventing monopoly risks, all with the goal of restoring dynamic balance between supply and demand.

4. Conclusion

The long-term logic of solar has not fundamentally changed. However, the industry has clearly moved from a manufacturing-led expansion phase into a system-constrained phase. Increasingly, the ability of power systems to absorb and deliver incremental generation will determine whether installations translate into effective output and realizable returns.

For China’s PV industry, its role as the global supply hub remains a structural advantage. Yet with demand growth slowing and supply inertia still present, the rebalancing process is likely to involve a longer period of volatility.

Policy direction toward “anti-involution” should help push the market toward a healthier supply-demand balance, but translating this framework into visible profit recovery and stable pricing will take time and require clearer confirmation signals.

At this stage, we prefer a framework of “long-term tracking, tactical patience.” In other words, the sector remains structurally important, but from an allocation perspective it may be more prudent to wait for higher-conviction turning points. For most investors, maintaining patience and a modest distance may offer a better balance between risk and reward.