How Legal Systems Shape the Longevity of Wealth?

If you track the world’s great family fortunes across a century, a stark pattern appears: some surnames return generation after generation, while others disappear within a decade of the founder’s death. People often attribute this to entrepreneurial skill, investment foresight or family culture. In our daily work with wealthy families, however, another determinant consistently stands out—the legal system beneath the wealth, which quietly governs who must inherit, how assets can be protected, and how long wealth can realistically survive.

Two families with the same net worth can experience dramatically different outcomes depending on where they are located. In common-law jurisdictions, trusts and wills allow the elder generation to shape multiple generations of incentives, protections and governance. In civil-law jurisdictions, the law may enforce mandatory shares for close relatives and override parts of a carefully drafted plan regardless of the founder’s intentions. Add multiple citizenships, foreign marriages and assets across continents, and succession quickly becomes not a financial question but a legal-infrastructure question.

This article highlights how legal systems shape the life span of wealth, comparing common-law and civil-law traditions; examining Hong Kong, Singapore, Switzerland and Taiwan as wealth-holding jurisdictions; and addressing a rising issue in Asia: non-U.S. parents with U.S.-citizen children and the important role trusts still play.

I. Wealth’s Life Span Is a Legal Question Before It Is a Financial One

Investment performance matters, but over several generations, the trajectory of family wealth depends on a simple equation:

Wealth creation × Wealth preservation × Wealth transition

The first two relate to entrepreneurship, discipline and market conditions.

The third — wealth transition — is shaped almost entirely by law:

• who must legally receive a minimum share;

• whether trusts are recognised and enforceable;

• how assets are treated upon deceased;

• whether cross-border planning will be honoured;

• whether estate and gift taxes accelerate wealth erosion.

Legal systems function like the operating rules of a game. Some give families broad discretion to design long-term outcomes. Others impose hard-coded rules—such as compulsory inheritance rights—that restrict multi-generation planning. Understanding these differences is essential to any serious family-governance strategy, and often explains why some fortunes endure while others dissipate.

II. Common Law vs Civil Law: Two Opposite Worldviews

1. Common law: freedom of disposition

In common-law jurisdictions—Hong Kong, Singapore, England—the principle of testamentary freedom is central. A testator may leave most or even all assets to anyone, provided formalities are met. Adult children have no automatic right to inherit.

This flexibility is reinforced by the trust system, one of the most powerful tools for long-term governance and asset protection. A trust separates legal from beneficial ownership: assets held by trustees are ring-fenced from their personal estate and managed under fiduciary duties for beneficiaries.

Hong Kong’s Trustee Ordinance (Cap. 29), modernised in 2013, strengthened trustee powers and beneficiary rights, making Hong Kong trusts highly adaptable for complex, multi-jurisdictional families. Courts in common-law jurisdictions ordinarily respect wills and trust deeds unless they violate public policy or fail to make minimal maintenance under family-provision statutes. The underlying philosophy is contractual freedom and structural flexibility.

2. Civil law: protection of close family

Most civil-law jurisdictions—Switzerland, France, Spain—follow forced heirship, ensuring that spouses and children receive a legally mandated portion of the estate.

Switzerland’s 2023 inheritance reform reduced descendants’ forced share from three-quarters to one-half of their statutory portion and removed parents as forced heirs. Still, in a typical family structure, around half of all assets must be reserved for compulsory heirs.

Civil-law systems promote fairness and mitigate the risk of exclusion, but the trade-off is fragmentation of assets with each generation, making it difficult to preserve concentrated holdings or maintain long-term compounding.

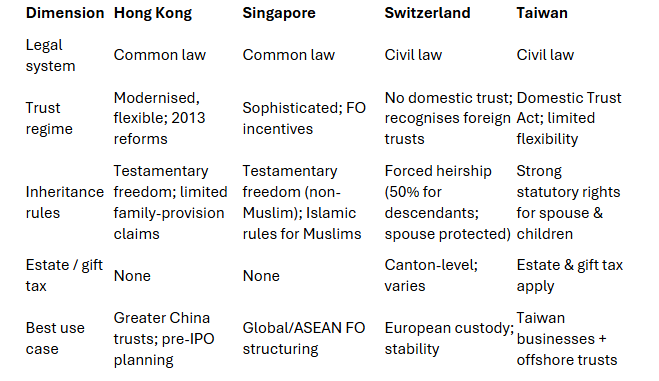

III. Hong Kong, Singapore, Switzerland and Taiwan: Four Legal Platforms for Wealth

1. Hong Kong: flexibility, simplicity and strong trust capability

Hong Kong offers:

• strong testamentary freedom,

• a mature and modernised trust regime,

• no estate duty, no gift tax and no general capital gains tax.

These features give families substantial design space for multi-generation trusts, shareholding structures, pre-IPO planning and philanthropic governance. For families with Mainland China exposure, Hong Kong also provides cultural proximity and reliable legal predictability.

2. Singapore: regional hub with regulatory precision

Singapore mirrors common-law flexibility and complements it with:

• zero estate, inheritance and gift tax since 2008;

• a sophisticated trust and fund ecosystem;

• increasingly robust substance and governance expectations after recent AML reforms.

This blend of tax neutrality and institutional credibility has made Singapore a preferred base for global and ASEAN families seeking long-term, compliant structures.

3. Switzerland: civil-law stability with global trust integration

Switzerland blends a civil-law forced-heirship framework—made more flexible by the 2023 reform—with a decentralised tax system. Switzerland does not levy federal inheritance or gift tax. Instead, each canton sets its own rules. Many cantons exempt spouses, and some also exempt or apply reduced rates for direct descendants, but treatment varies by canton. This canton-based structure, combined with Switzerland’s political and financial stability, continues to attract international families.

Although Swiss law does not create a domestic trust, Switzerland has recognised foreign-law trusts under the Hague Trust Convention since 2007 and incorporates trust concepts into its private-international-law and bankruptcy frameworks. As a result, families frequently structure trusts under English, Jersey or Cayman law while placing custody and portfolio management in Switzerland to combine trust flexibility with European financial access.

4. Taiwan: civil-law inheritance with developing trust practice

Taiwan represents another variant of the civil-law model. Its Civil Code grants spouses and children statutory inheritance rights, which limits long-term concentration of wealth across generations.

Taiwan’s Trust Act provides a basis for private trusts, but the industry is largely bank-operated, resulting in more standardised structures and less flexibility than common-law trusts. Courts may apply substance-over-form analysis in certain disputes. Estate and gift taxes apply at progressive rates.

For families with Taiwanese business operations, domestic trusts are useful for liquidity and philanthropy. For multi-generation planning, however, many families adopt a hybrid model: operational assets remain in Taiwan, while long-term financial assets are structured through Hong Kong or Singapore trusts.

IV. Comparison Table

V. When the Children Are U.S. Citizens: Trusts as Cross-Border Architecture

A common scenario in Asia:

Parents are non-U.S. persons; children are U.S. citizens or U.S. green-card holders.

1. U.S. citizens are taxed on worldwide income

Regardless of residence, U.S. citizens must report and pay tax on worldwide income. U.S. rules governing “foreign trusts” are among the most complex globally. Where a U.S. beneficiary or deemed U.S. owner exists, extensive filings such as Forms 3520 and 3520-A may be required.

Foreign non-grantor trusts can trigger throwback taxes on accumulated income, recharacterising it as if earned in prior years and imposing interest charges.

Thus, directly gifting offshore assets to U.S. children often causes:

• ongoing U.S. reporting obligations;

• U.S. estate and gift tax exposure;

• full transparency under FATCA and CRS;

• misalignment with family-governance objectives, including vulnerability to divorce, creditors or poor financial decisions.

2. How trusts provide solutions

Despite these constraints, well-designed foreign trusts remain essential tools for cross-border families—not for secrecy, but for creating a coherent, compliant and durable governance structure.

A. A buffer between legal systems

A trust consolidates ownership into a single structure. Upon the parents’ passing, transitions occur within the trust—not through multiple probate processes—reducing conflict with civil-law forced heirship and cutting administrative complexity.

B. Behavioural governance and intergenerational discipline

A trust enables parents (or a family council) to define:

• how, when and under what conditions assets are accessed;

• protections against divorce or creditor claims;

• education and professional milestones;

• entrepreneurial support without ceding full control.

These guardrails often matter more than taxes in ensuring wealth survives into future generations.

C. U.S. tax timing and allocation (always within compliance)

Through careful structuring:

• Foreign Grantor Trusts (FGTs)

allow income to be taxed to the non-U.S. parent while alive.

• Foreign Non-Grantor Trusts (FNGTs)

allow long-term accumulation with controlled distributions to U.S. beneficiaries.

• Clean capital strategies

separate pre-immigration assets from taxable income streams.

These tools help manage when and how U.S. taxes apply.

D. Centralised cross-border compliance

Professional trustees coordinate FATCA, CRS and local filings, maintain documentation, and interact with financial institutions—reducing risk and administrative burden for younger U.S. beneficiaries.

E. Long-term asset protection and continuity

Trust-held assets are:

• shielded from marital breakdown,

• less vulnerable to creditor claims,

• protected from mismanagement or family disputes,

• governed by a structure that survives death, incapacity or relocation.

VI. Trusts Are Powerful—but Not a Panacea

Although trusts can be effective for multi-jurisdiction wealth planning, they are not without limitations. Families should recognise that a trust is a sophisticated legal structure requiring ongoing commitment, coordination and governance. Administrative costs—including trustee fees, legal reviews, tax filings and compliance—can be significant, particularly for arrangements spanning several jurisdictions. Trusts also demand clarity of intention: poorly drafted deeds, unclear letters of wishes or ambiguous beneficiary provisions may create disputes rather than prevent them.

Another practical constraint is limited flexibility. Once assets are transferred into a trust, unwinding or materially amending the structure can be difficult, especially if beneficiaries’ consent is required or if local law restricts variations. A trust that is too rigid may fail to adapt to changes in family dynamics, tax laws or business circumstances. Conversely, a trust that grants excessive discretion without proper guardrails may dilute the settlor’s original intent.

Moreover, the effectiveness of a trust depends heavily on jurisdictional alignment. Some civil-law countries may apply substance-over-form analysis, potentially challenging transfers if creditors or heirs argue lack of intent or improper purpose. In the U.S. context, foreign trusts involving U.S. beneficiaries face additional complexity: compliance failures can result in substantial penalties and, in some cases, unfavourable tax treatment. Trusts can also unintentionally create distance between family members and their assets if governance mechanisms are overly rigid or communication with trustees is insufficient.

In short, while trusts provide structure, protection and long-term continuity, they work best when supported by active family involvement, regular legal updates, and a clear governance philosophy. They are a tool—not a substitute—for thoughtful family leadership.

VII. Conclusion: Choose the Legal System Before the Assets

Hong Kong, Singapore, Switzerland and Taiwan each offer distinct legal environments for long-term family wealth. Choosing among them—or combining them intelligently—requires addressing deeper questions:

• How concentrated should wealth remain across generations?

• How much freedom versus structure should the next generation receive?

• Does our current legal base support our long-term governance goals?

If not, the solution is not merely portfolio rebalancing—it is legal rebalancing: choosing the governing law of trusts, where assets are held, and where the family office is located so that these systems reinforce rather than contradict one another.

Ultimately, the legal system itself is one of a family’s most powerful—yet often overlooked—intangible assets. How well it is chosen and used will determine whether a fortune lasts one generation, or endures across several.