Fed Observation: Who Votes Matters More Than Who Chairs

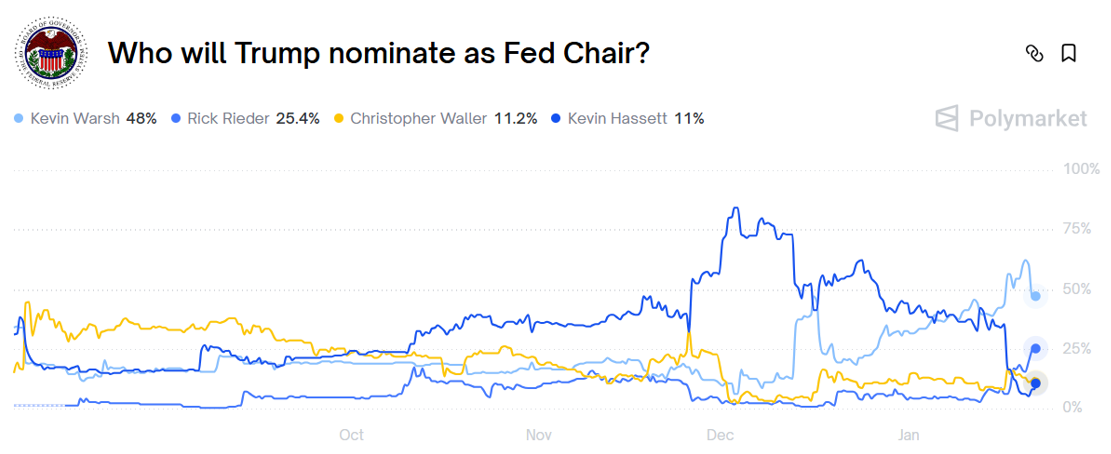

Jerome Powell’s term as Chair of the Federal Reserve is set to expire in May 2026. As that date approaches, President Donald Trump has once again turned what is usually a discreet, institution-heavy process into something closer to prime-time political theatre. The shortlist is getting shorter. Betting markets keep updating the odds.

The Shortlist, Minus One

At the center of the debate are four names that matter—and one that no longer does.

Kevin Hassett: Close Alignment, Market Discomfort

Kevin Hassett was, until recently, a serious contender. As a long-time Trump ally and current head of the National Economic Council, he checked the loyalty box with room to spare. However, Hassett’s proximity to the White House made him look less like a central banker and more like an extension cord. With Trump signaling a preference to keep him at the NEC, Hassett is effectively out of the picture.

This matters. With Hassett sidelined, the most acute threat to perceived Fed independence fades materially.

Rick Rieder: The Market Insider (and the Confirmation-Speed Bump)

Rick Rieder—BlackRock’s global fixed income CIO—is the only finalist with no Federal Reserve or government experience, which can read as either refreshing or alarming depending on whether you think monetary policy is best run by technocrats or by people who have actually traded through a term premium.

Rieder’s appeal is straightforward: he speaks fluent markets, has spent a career stress-testing policy regimes in real time, and tends to frame the Fed’s job around stability rather than heroics. The complication is equally straightforward: Senate confirmation tends to be tougher for candidates with deep market experience but limited government or central banking backgrounds.

Kevin Warsh: Reformist Credibility, With a Hawkish Memory

Kevin Warsh remains a formidable candidate. A former Fed Governor with deep Wall Street experience, he offers intellectual firepower, institutional memory, and a clear appetite for reform—particularly around the Fed’s balance sheet and what he views as mission creep. For markets, Warsh represents a familiar trade-off: credibility and independence on one hand, a not-so-distant hawkish past on the other. Warsh may have shifted toward a more dovish tone, but markets will need proof over time. His appointment would probably be seen as constructive, though not as an immediate green light for faster cuts.

Christopher Waller: The Credible Clean Solution

Christopher Waller is the least theatrical option—and precisely for that reason, the most effective.

As a sitting Fed Governor appointed by Trump, Waller offers continuity without capitulation. He has been consistently data-driven, openly supportive of rate cuts when justified by macro conditions, and—crucially—publicly committed to central bank independence. His dovish tilt has been earned through analysis rather than political alignment, which gives him something rare in this cycle: credibility with both markets and institutions.

The case for Waller is not that he promises faster cuts. It is that when cuts come, markets will believe they are warranted. That distinction matters. Financial markets have already shown a preview of their reaction to Waller’s thinking: lower yields, firmer risk sentiment, and less noise around institutional risk premium. In a world where volatility increasingly comes from headlines rather than data, Waller represents a form of policy hedging.

If Warsh represents reform, and Hassett represented control, Waller represents stability—delivered without stagnation, and without headlines that force investors to reprice institutional risk.

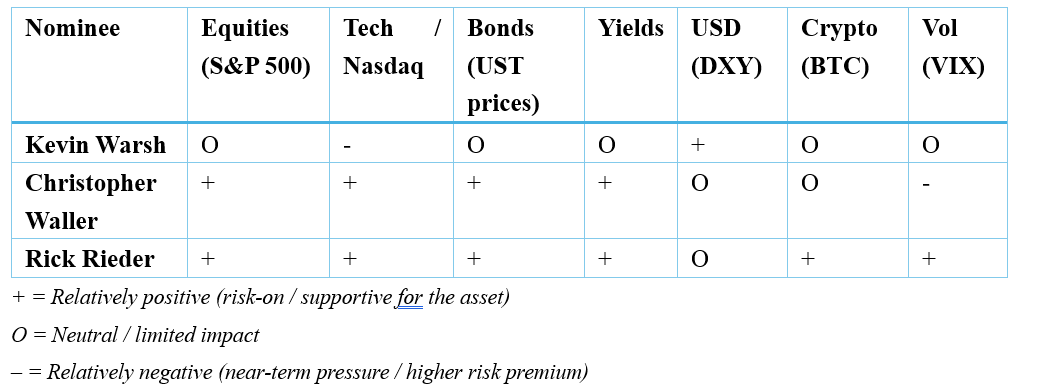

What This Means for Markets?

From a market perspective, the key differentiator among the candidates is not the direction of policy—lower rates are broadly expected in 2026 under all scenarios—but the credibility of the transmission mechanism.

A Waller nomination would likely be the most stabilizing outcome, as it reinforces continuity, data dependence, and Federal Reserve independence. Markets tend to reward this combination with lower risk premia: equities and duration benefit, the dollar remains range-bound, and volatility compresses as policy uncertainty recedes. Warsh, by contrast, offers credibility through reform and institutional experience, but his historical hawkish imprint may temper expectations for aggressive easing, leading to a more nuanced response across assets, particularly in rate-sensitive growth stocks.

A Rieder nomination would be the most market-friendly on first reaction, reflecting strong confidence in his understanding of financial markets and policy transmission. Risk assets and crypto would likely respond positively in the near term, and bonds could benefit from expectations of pragmatic easing. That said, this scenario also carries higher “optics risk”: confirmation friction, conflict-of-interest narratives, and headline volatility could partially offset the initial relief rally.

Overall, the market takeaway is that while each candidate implies a different path for volatility and risk premia, none fundamentally alters the underlying outlook—2026 monetary policy remains driven by incoming data, not personalities.

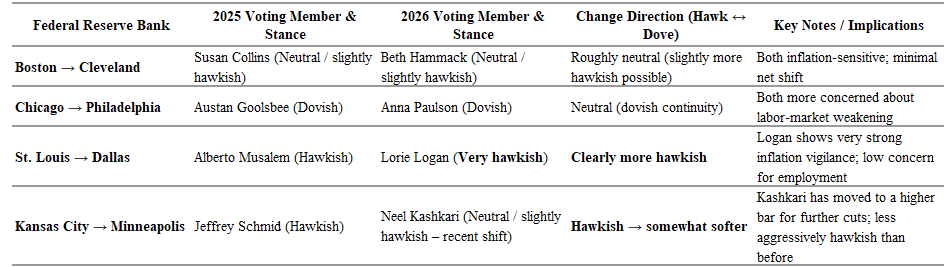

The real problem is Trump’s Fed Overhaul, Not Just the Chair

As we said in our U.S. Macro Outlook, our core view is simple: the committee matters more than the Chair. 2026 is a turning point for Fed policy—not just because the Chair may change, but because the voting lineup changes at the same time. Regional Fed presidents rotate into voting seats each year, and there may also be openings on the Board of Governors. Put differently: markets are not only watching who wears the Chair badge—they are watching who gets to vote.

FOMC Structure (Quick Refresher)

The FOMC has 12 voting members:

• 7 Governors (including Chair and Vice Chair),

• The President of the New York Fed (currently John C. Williams, generally viewed as dovish/market-stability oriented),

• 4 rotating regional Fed Presidents, which change each year.

For 2026, the rotating regional voters are: Cleveland, Philadelphia, Dallas, and Minneapolis.

What is predictable

The 2026 rotation remains net slightly hawkish, mainly due to the significant upgrade in hawkishness from Musalem → Logan (Dallas seat), only partially offset by the moderation from Schmid → Kashkari (Minneapolis seat). Dovish continuity in the Chicago → Philadelphia swap helps limit the overall tightening pressure.

Less Predictable and More Market-Critical Changes

• The Miran seat (a known vacancy, but an uncertain impact).

Governor Stephen Miran’s term expires on January 31, 2026, creating the only Board vacancy the White House can plan for with certainty. This seat is especially important if the next Fed Chair is chosen from outside the current Board, as it could be used to “slot in” a preferred nominee or another policy-aligned Governor. From a market perspective, timing matters: a rapid appointment could tilt the Fed more dovish and reinforce expectations of earlier easing, while a delayed fill would keep the committee closer to its current balance and limit near-term policy shifts.

• The Lisa Cook case (low probability, high impact).

Governor Lisa Cook’s term runs through 2038, but her position has become a legal flashpoint after the Trump administration attempted to remove her in 2025 over alleged mortgage-application fraud. The legal issue centers on the definition of “for-cause” removal under the Federal Reserve Act. While precedent has historically favored strong protections for Fed independence, any broadening of this standard would be significant. If Cook were ultimately removed, it would open an additional Board seat and raise immediate concerns about politicization.

Independence is what markets are really pricing. Markets can handle rate cuts; they struggle with rate cuts that look politically driven. What Trump appears to be pursuing is less a frontal assault than a tactical “step back to step forward”—creating enough pressure and ambiguity to expand the White House’s influence over the Fed. Whether through efforts to remove Governor Lisa Cook or the Justice Department’s preliminary criminal inquiry tied to the Fed headquarters renovation, the situation has become increasingly complex—and, importantly for markets, increasingly headline-driven.

A more “acceptable” Chair choice—someone conservative-leaning yet institutionally credible, such as Kevin Warsh or Christopher Waller—starts to look like a workable compromise. Such a compromise could give Powell a face-saving exit path, smooth the nomination through the Senate, and reduce the immediate independence risk premium that markets have been watching. But it may also have a second-order implication: if the process results in Powell stepping aside from the Board and freeing up an additional Governor seat, it creates room for the administration to appoint another loyalist. Over time, that’s how you shift the committee’s center of gravity—quietly, through seat math rather than speeches.

The Waller Seat “Side Effect”

One nuance that often gets missed: if Christopher Waller is appointed Chair, that can create an additional opening on the Board, meaning the administration may gain one more seat to fill. Even if Waller himself is seen as credibility-friendly, that extra seat could gradually shift the committee’s center of gravity over time, giving the White House more influence over future votes.

Conclusion

Putting the pieces together, the 2026 Fed story is less about a single “winner” in the Chair race and more about how the voting math and institutional guardrails evolve at the same time. With Kevin Hassett effectively out of the picture, the most direct politicisation risk seems reduced, and a Waller- or Warsh-type outcome would likely keep the Fed’s operating framework broadly intact. Our base case is still two rate cuts in 2026, but we are now leaning toward three— determined by the balance between labor-market cooling and inflation persistence.

For term structure, that implies a split: the front end should still trade mostly on data and near-term policy expectations, while the long end is more exposed to term premium repricing when independence is questioned—showing up as long-end volatility. Our conviction expression remains the 5–7 year “belly” of the curve. In other words, the front end is about the path of cuts; the long end is about the credibility of the process.

For investors, the setup is therefore familiar, but the uncertainty is not. The Fed will respond to what the data say about growth, jobs, and inflation; the uncertainty is how much political noise gets attached to that process—and whether it changes the market’s confidence in the institution. In other words: rates will move on macro; volatility will move on governance headlines.