When “Public Data” Becomes Radioactive

For years, the tech industry celebrated the phrase “data is the new oil.” It was meant as praise — a way to elevate information to the status of the world’s most valuable resource. But oil is not free for the taking. It is owned, regulated, and licensed. Data, meanwhile, has long been treated as atmospheric — floating freely online, available to anyone with a scraper or API key, as though visibility implied permission.

That illusion has now shattered. Public data is no longer free. What once felt like open territory is being reclassified as private property, shielded by contract law, privacy regulations, and platform licensing agreements. In this emerging landscape, data is no longer merely oil; it has become akin to uranium. While it retains immense power, it is also inherently hazardous. Mishandling it can inflict severe damage on the companies that depend on it.

This raises a pivotal question for this new era: If data is publicly visible, do you genuinely possess the right to use it, or are you unknowingly trespassing?

The Silent Rule That Governed the Internet

For much of the internet's evolution, businesses adhered to an unspoken principle: if content is publicly accessible, it is fair game for collection, analysis, and repurposing. Anything posted online was implicitly deemed available for exploitation. Hedge funds extracted consumer sentiment from restaurant reviews, HR analytics tools scraped LinkedIn to monitor employee turnover, search engines replicated entire websites under the guise of indexing, and AI developers integrated millions of blog posts, comments, selfies, and forum discussions into their training datasets.

Few voiced objections, and those who did were often dismissed as individuals who “didn’t understand how the internet works.” However, there was a broader awareness; the challenge lay in the absence of legal recourse. That dynamic has now shifted.

Three Forces That Have Ended the Free-for-All of Public Data

The transition away from the ethos of "scrape now, ask for forgiveness later" was not driven by a sudden moral awakening but rather the confluence of legal, economic, and platform dynamics.

• Legal Frameworks Caught Up with Practice: Courts across the United States, Europe, and Asia have begun to explicitly rule that visibility does not equate to consent. Public accessibility is not synonymous with public domain. Copyright protections remain in effect, privacy rights are upheld, and contractual restrictions—such as platform Terms of Service—are increasingly enforced as legally binding agreements.

• Platforms Started Charging Rent: When Twitter raised its enterprise API pricing to $42,000 per month, it was more than monetization; it signaled a shift in perception, indicating that tweets are no longer free public speech but rather licensed content. Reddit followed suit by imposing charges for bulk access, while LinkedIn tightened its restrictions on exporting profile data following its legal victory against hiQ Labs. Platforms have transitioned from neutral intermediaries to landlords.

• Regulators Reframed Data as Personal Identity: In cases such as Clearview AI, which scraped billions of social media images for facial recognition purposes, privacy authorities intervened not on copyright grounds but through biometric regulations. Their stance is unequivocal: your face belongs to you, even when shared publicly. It is not an open dataset for someone else’s algorithm.

The message is now unmistakable: the era of unlicensed data extraction is coming to an end.

What Constitutes “Fair Use”?

Many companies continue to dismiss concerns by invoking “fair use” as a blanket defense. They operate under the assumption that as long as they do not explicitly resell raw data, their usage must be permissible. However, that is a misinterpretation of the law.

Courts assess fair use through four critical factors:

1. Transformative Use: Did the usage create new meaning or function? Simply copying an entire article or image to train a system does not inherently qualify as transformative. True transformation requires commentary, criticism, parody, or significant recontextualization. Silent ingestion rarely meets this criterion.

2. Nature of the Source Material: Is the source material creative or factual? User-generated content—whether a Yelp review or a personal photo—is generally considered creative expression, which receives higher protection. Scraping factual government tables is one thing; ingesting someone’s life story is another.

3. Amount Taken: Was only the necessary amount extracted? Fair use favors precision over volume. Bulk scraping of millions of posts almost invariably exceeds what courts deem reasonable.

4. Market Harm: Did the reuse harm the original source’s economic market? If your system allows users to obtain answers without visiting the original source—such as summarizing paywalled journalism—courts may interpret that as market substitution.

These inquiries are no longer theoretical; they are actively being tested in litigation.

Legal Turning Points Redefining “Public Data”

Three landmark cases have unequivocally established one principle: public visibility does not equate to lawful usage. Collectively, they have instigated a structural shift in how data must be acquired, licensed, and defended.

1. The New York Times v. OpenAI & Microsoft: The First Copyright Battle Between AI and Journalism

The New York Times sued OpenAI and Microsoft, claiming that its copyrighted articles were used to train GPT models without permission. The key issue isn’t whether AI models can “read” the content; it’s whether they can reproduce it. Court documents revealed that GPT models were generating near-verbatim snippets from paywalled articles. If courts find this behavior to be systemic, the entire “transformative use” defense could fall apart. Should OpenAI be required to pay licensing fees, it could force other AI companies to follow suit.

2. Getty Images v. Stability AI: When Watermarks Became Legal Forensics

Getty Images took legal action against Stability AI in both the U.S. and UK after discovering that AI-generated images contained distorted versions of the Getty watermark. Getty’s argument is straightforward: AI doesn’t erase copyright infringement; it highlights it. The presence of damaged watermarks serves as proof that copyrighted material was used in training without proper abstraction. If Getty wins, visual licensing will shift from being a courtesy to a legal requirement.

3. LinkedIn v. hiQ Labs: The End of “Public Means Free to Take”

hiQ Labs, a startup analyzing employee turnover, scraped data from publicly accessible LinkedIn profiles. LinkedIn responded with a cease-and-desist order, leading to a lengthy legal battle. hiQ argued that scraping was fair game since the profiles were publicly visible. LinkedIn countered that this was a breach of contract and pointed to its Terms of Service. The courts ultimately sided with LinkedIn, establishing a crucial precedent: Terms of Service are enforceable licenses, and even public pages aren’t necessarily in the public domain.

The outcomes of these cases are reshaping the norms of digital commerce. The law no longer queries whether data is accessible; it now evaluates whether you were authorized to use it.

Ownership, Not Volume, Is the Only Sustainable Defensibility

For years, companies equated scale with strength. The premise was that whoever possessed the most data could build the best models and gain a competitive edge. That logic is now legally inverted. The larger your dataset, the greater your liability—unless you can demonstrate lawful title.

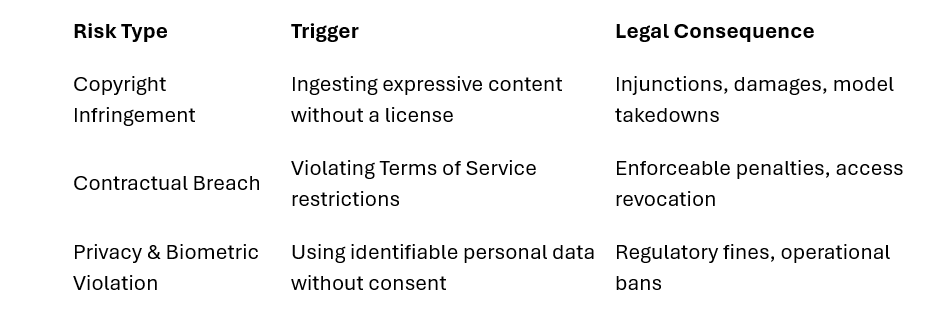

Modern data risk manifests across three primary fault lines:

Any one of these risks can paralyze a product line. When combined, they create cascading exposure—a scenario where the entire dataset or model stack becomes contestable, not just its outputs.

This underscores why data provenance—the ability to document the origin of data, the terms under which it was acquired, and for what permissible use—is evolving from a compliance luxury to a legal necessity.

Lawful Data Strategy: An Architectural Imperative

Appeals to “fair use,” “internal testing,” or “public domain” are no longer viable defenses. Companies that aim to scale must adopt explicit data acquisition models.

At minimum, three defensible architectures exist:

1. Licensed Acquisition: Contract as a Competitive Advantage

Negotiate direct access from platforms, publishers, or data cooperatives. While more costly than scraping, this approach ensures legal certainty and differentiation.

2. Consent-Based Collection: Users as Principals, Not Exhaust

Implement clear permission frameworks where users grant tiered rights in exchange for value—treating participation as a partnership rather than mere extraction.

3. Federated or Synthetic Training: Compute Where the Data Lives

When data cannot be centralized, send models to it—or train on statistically generated proxies. Ownership is supplanted by licensed influence, not possession.

Companies employing these models are not slower; they are more resilient, more acquirable, and more insurable. That is the critical advantage in regulated markets.

A New Investment Discipline: Data Rights as an Asset Class

For over a decade, investors evaluated AI companies primarily on model performance—accuracy, inference speed, unit economics. Those metrics are now insufficient. A high-performing model trained on unlawfully sourced data is not an asset; it is a pending injunction.

Every serious investor must now ask:

1. What percentage of your data is held under explicit license, documented consent, or statutory exemption?

2. Can you produce a traceable ledger of data provenance?

3. If challenged, can you defend your model weights as lawfully derived—not merely technically superior?

The parallel to software licensing is direct. Just as no responsible investor would fund a company built on copied code, no serious capital will back a model trained on questionable data.

Data rights are evolving into intellectual property rights. And IP rights govern transferability, enforceability, and exit viability.

Conclusion

The era of “move fast and scrape things” is over. The public web is no longer a lawless frontier; it has been subdivided into contractual estates, privacy zones, and proprietary holdings.

The winners of the next decade will not be the boldest extractors but rather the most disciplined custodians—those who do not merely collect data but own it, license it, and defend it.

Data may still power the most valuable enterprises of the century, but it is no longer crude oil; it is fissile material—potent but unforgiving.

In such an environment, advantage will not belong to those who move the fastest, but to those who move with legitimacy.